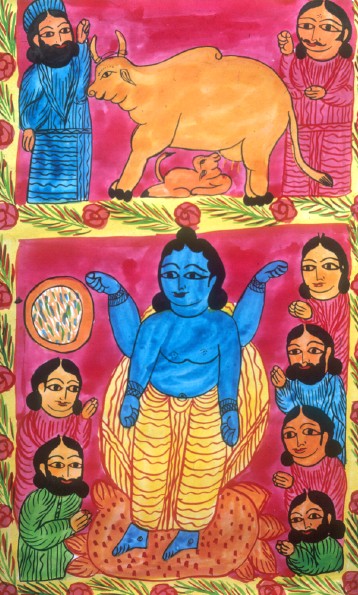

Manasa Mangal, (Bipradas Pipalai 1545 AD) a medieval Bengali classic about the serpent-goddess Manasa. These stories related to mythology are the main elemnets of the Pat-chitra culture.

Manasa Mangal, (Bipradas Pipalai 1545 AD) a medieval Bengali classic about the serpent-goddess Manasa. These stories related to mythology are the main elemnets of the Pat-chitra culture.

Patuas, like the kumars, started out in the village tradition as painters of scrolls or pats telling the popular mangal stories of the gods and goddesses. For generations these scroll painters or patuas have gone from village to village with their scrolls or pat singing stories in return for money or food. Many come from the different villages of Bengal. The pats or scrolls are made of sheets of paper of equal or different sizes which are sown together and painted with ordinary poster paints. Originally they would have been painted on cloth and used to tell religious stories such as the medieval mangal poems. Today they may be used to comment on social and political issues such as the evils of cinema or the promotion of literacy.

Mangal kavyas are auspicious poems dedicated to rural deities and appear as a distinctive feature of medieval Bengali literature. Mangals can still be heard today in rural areas of West Bengal often during the festivals of the deities they celebrate, for example Manasa puja in the rainy season during July-August when the danger of snake bite is at its peak. Interestingly, it is the mangal stories connected with this particular art form that provide us with some of the earliest clues about the worship of clay images in Bengal.

The two most famous poems in this respect are the Chandi Mangal and the Manasa Mangal. In the Chandi Mangal of the Bengali poet Mukundarama Chakravarti (16th c), known as Kavikankana, the village goddess Chandi takes on the form of the Puranic deity Mahisasuramarddini (Durga) before the startled eyes of the hunter Kalketu and his wife.

Chandika took the form of Mahisasuramarddini In eight directions the Ashtanayikas shone forth

Her right foot rested on the back of a lion

Her left foot on the back of the demon Mahisha

With her left hand she held Mahisha's hair

With her right hand she placed her trident in his chest

On her left side shone her matted locks

Her headress encompassed the whole circle of the sky

Bracletes and armlets adorned her ten arms

In this form she receives puja from the whole world

A noose, a goad, bell, mace and bow

These five weapons gleam in her five left hands

A sword, discus, trident, spear and brightly-shining arrows

In her right hands gleam these weapons

To her left is Karttikeya, to her right Ganesa

Above, Shiva rides on the head of a bull

To her right is Laksmi, to the left Sarasvati

Facing her, deities sing various hymns

Her limbs outshine molten gold

The colour of her three eyes outcolours blue lotuses

And her face outshines the autumnal moon.

(Kavikankana Chandi)

What this mangal poem hints at is that the style of Durga images seen today in the clay images of Bengal was already popular in the 16th c. Durga is popularised as the beleagured wife of the farmer god Shiva. She may be the mighty awe-inspiring goddess who kills demons, but she is also the compassionate mother or Ma and the devoted daughter who returns home during the autumnal festival of Durgotsava. Throughout mangal literature, the village deities are shown as very accessible figures who communicate freely with mortals and share their griefs and delights.

|  |  |

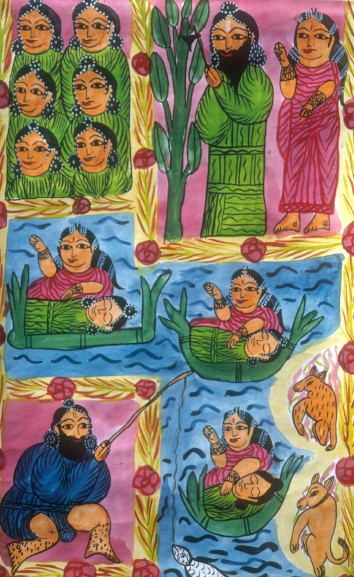

Tha main part of the mangal concerns the fate of Lakhindar and his bride Behula. Manasa warns that Lakhindar will die on their wedding night. So Chando has an iron room built to keep out any snakes that might kill his only son. However, Manasa persuades the architect to leave a gap big enough for one of her deadliest snakes to squeeze through at night and bite Lakhindar as he sleeps. Behula wakes up too late to help her newly-wed husband.

In this pat the snake goddess Manasa sends a poisonous snake to kill the hero Lakhindar while his wife Behula looks on helplessly. The iron room made to protect them on their wedding night proves useless.

The distraught Behula scolds Chando for his quarrel with Manasa and returns her wedding gifts. Instead of cremating her husband's body and scattering his ashes in the river as is the Hindu custom, she sets off downriver in a desperate bid to persuade to gods to revive her husband so that she avoids the fate of being made a young widow

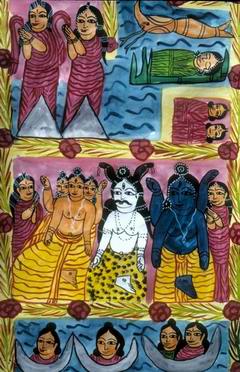

Manasa pat shows how Behula sets off downriver on a raft made of banana bark carrying her husband's corpse on her lap hoping to persuade the gods to revive Lakhindar. On the way she meets the fisherman Goda who taunts her but Behula replies that she worships only the mother Manasa and she floats off again downstream. Further on, she visits the city of the gods where she meets the gods Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva who are impressed by her skills as a dancer and washerwoman to the gods. Shiva decides to persuade Manasa to revive Lakhindar and his six brothers in return for persuading Chando to worship the snake goddess.

The Snake Litanies

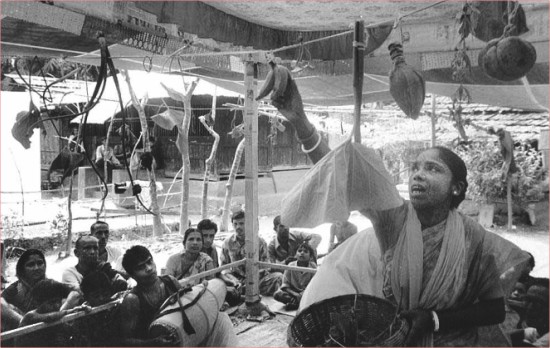

About ten kilometers to the south of Rangpur, in the village of Fatehpur the widows have a tradition of singing these songs about Manasa, or snakes. It is said that not everybody can appreciate this art. After receiving the letter from my friend Nurunnabi Shanto, I got the strong desire to go and see this performance by the widows. I was particularly excited because I had never before seen women perform this Manasa Mangal ritual. And yet, Manasa naturally seems like a woman's territory. But in the performances that I had seen before, there were no actual women. The female roles were played by men. So why were the women of Rangpur an exception? A hundred possible explanations came to my mind; I couldn't decide. I couldn't wait to visit Fatehpur village. But the first thing on my pre-set itinerary was visiting Pirojpur, Bagerhat. My Rangpur trip then, had to come later.

About ten kilometers to the south of Rangpur, in the village of Fatehpur the widows have a tradition of singing these songs about Manasa, or snakes. It is said that not everybody can appreciate this art. After receiving the letter from my friend Nurunnabi Shanto, I got the strong desire to go and see this performance by the widows. I was particularly excited because I had never before seen women perform this Manasa Mangal ritual. And yet, Manasa naturally seems like a woman's territory. But in the performances that I had seen before, there were no actual women. The female roles were played by men. So why were the women of Rangpur an exception? A hundred possible explanations came to my mind; I couldn't decide. I couldn't wait to visit Fatehpur village. But the first thing on my pre-set itinerary was visiting Pirojpur, Bagerhat. My Rangpur trip then, had to come later.

Behula

|

Royani:

Royani is the music of Manasas. It is the music of Behula.” At Meeradi's words I come back to the topic of Manasa, she seemed to make perfect sense. Of course, the songs were about the two women- Manasa and Behula. Both of these women have had to overcome many obstacles to be well respected in society. Men do not understand the pain and anguish these women have had to go through. One woman has many forms-the mother, the daughter, the sister.The whole performance was about the self-image and self-perception of these women. In that way, the show was kind of autobiographical. The whole performance is about singing and dancing. And throughout the performance the women of the whole village tirelessly performed the whole night, but in a manner as mundane as their lives. There were no frills. It seemed as though the show was inseparable from their lives- it was nothing special. For these women, performing is not much different from doing everyday chores like cooking. They all routinely get up to make rafts out of tree trunks as if they have done this many times before. Behula and Lakhshmindar get up on the raft and sail off. Lakhshimdar had been bitten, and bite victims must be put on a raft and sent away. Behula accompanied him as a perfectly virtuous wife. At this point in the performance, we feel the pain of Behula. The story of Behula is well known in Bangladesh. But this performance opens ones eyes to other things. Other sociocultural aspects come through in the way the performance unfolds, that one cannot understand from just casually hearing about the story. My experience at Rangpur was unique. The evening did shed light on the lives of these women, what songs mean to them and their lives (Simon Zakaria, Daily Star, July 21, 2007).

The whole performance is about singing and dancing. And throughout the performance the women of the whole village tirelessly performed the whole night, but in a manner as mundane as their lives. There were no frills. It seemed as though the show was inseparable from their lives- it was nothing special. For these women, performing is not much different from doing everyday chores like cooking. They all routinely get up to make rafts out of tree trunks as if they have done this many times before. Behula and Lakhshmindar get up on the raft and sail off. Lakhshimdar had been bitten, and bite victims must be put on a raft and sent away. Behula accompanied him as a perfectly virtuous wife. At this point in the performance, we feel the pain of Behula. The story of Behula is well known in Bangladesh. But this performance opens ones eyes to other things. Other sociocultural aspects come through in the way the performance unfolds, that one cannot understand from just casually hearing about the story. My experience at Rangpur was unique. The evening did shed light on the lives of these women, what songs mean to them and their lives (Simon Zakaria, Daily Star, July 21, 2007).

...The Bridal Chamber of Behula is stand in the south 2 k.m. from Mohaastan garh, Rangpur, Bangladesh.

4. A tradition which ridicules the clash of civilisations

The Legend of Gazi

Gazi Pir was a Muslim saint who is said to have spread the Islamic religion in Bengal. According to local myth, he could control dangerous animals and make them harmless and gentle. He is shown riding a fearsome Bengal tiger while holding a poisonous snake in his hand without coming to any danger. He also battled with the crocodiles who were a constant threat to the people of the area called the Sunderbans, the watery jungle where the river Ganges meets the sea. Through his influence over all of these animals, he is said to have made it possible for people to live and farm in that jungle and people still pray to him to protect them while they go about their daily chores.

When we talk about patchitra, first of all, the images of Kalighater pats come in our mind. This genre of painting developed in the nineteenth century which flourished in the market places around the Kalighat Mandir on the bank of the Ganges in Kolkata. But according some historians, older than the Kalighater pat were Gazir pats which most probably emerged around the 16th century. Unlike the Kalighater pat, the uniqueness of Gazir pat is of profound importance and influence in the history of painting and literature in Bengal both in subject and form. The scroll paintings of Gazir pat (pat meaning cloth), present the valour of legendary figure Gazi Pir, who was respected and worshiped as a warrior-saint.

Gazir Pir is not mentioned in history, according to some scholars, the Muslim saint Gazi, might have appeared around the 15th century and seemed to be related to the rise of Sufism in Bengal. Islam Gazi, a Muslim general, served Sultan Barbak (1459-74) in Delhi and conquered Orissa and Kamrup (now Assam). Towards the end of the 16th century, Shaikh Faizullah praised the valour and spiritual qualities of this general in his verse Gazi Bijoy, the victory of Gazi.

To the worshipers of Gazi, this warrior-saint protected his devotees from attacks of wild animals and demons in the forests. In Bangladesh, particularly, in the regions of the Sundarban, the story and images of Gazi Pir had earned much popularity among the forest dwellers, like woodcutters, beekeepers and others. These communities still believe in the supernatural powers of the Pir and utter his name when they venture in to the forest.Gazi is worshiped as the protector against demons and harmful deities

In the plains, Gazi is worshiped as the protector against demons and harmful deities and saves them from all sorts of dangers. The villagers usually call the gayens or folksingers, who know the story of Gazi Pir to sing the saint? praise

The singers·preaching created a demand for the pats among the devotees, irrespective of caste, creed and community and the pats had gained a huge popularity in the rural areas across the country, in the early years. Traditionally, the singers were Muslims while the patuas belonged to the Hindu religion. Sadly, at present, this combined form of art, paintings on pats and rendering of Gazir praise, has lost its purpose as a savoir from evil.

Until the recent past, the narration of the story of Gazi Pir with the help of a Gazir pat was a popular form of entertainment in rural areas, especially in greater Dhaka, Mymensingh, Sylhet, Comilla, Noakhali, Faridpur, Jessore, Khulna and Rajshahi.

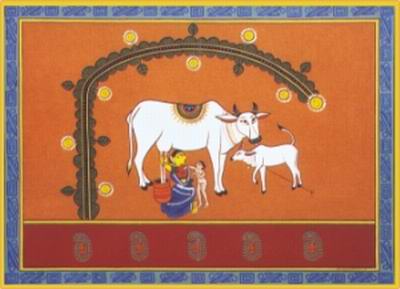

Gazir pat has specific images painted on a single canvas which have remained unchanged through the centuries. These images have been honoured as sacred symbols of good omen. There are twenty seven panels in a traditional Gazir pat, which measures 60 inches X 22 inches. The ankaiya (painter) follows the traditional styles in depicting the images. In the twenty-seven panels, the ankiya draws the images of a shimul tree; a cow; drum to depict triumph of Kalu Gazi; sawdagar or merchant; a deer being slaughtered; Asha or hope, the symbol of Gazi; Kahelia; Andura and Khandura; tiger; umbrella in the hand of Gazi disciple; Suk and Sari birds sitting on the umbrella; Lakhmi; charka, the spinning wheel; two witches; goala or milkman; mother of the goala; a cow and a tiger; an old woman beautifying herself; Baksila; Ganga; Jamdut; Kaldut; mother of Jam raja; and in the centre Gazi riding on a tiger. The singer or singers narrate sometimes the night long story, pointing at the characters, which appear in the twenty seven panels of the pat.Red and blue are the two pigments mainly used in the pats. There are slight variations of colour, with crimson and pink from red, and grey and sky-blue from blue. Every figure is flat and two-dimensional. In order to bring in variety, various abstract designs (such as diagonal, vertical and horizontal lines and small circles) are often used. Trees, Gazi mace, the tasbih or prayer beads, birds, deer, hookahs etc, are extremely stylised. The figures of Gazi, his disciples Kalu and Manik Pir, Jama (the Hindu god of death) messengers, etc appear rigid and lifeless. Though there is no attempt at realism in the images of Gazir pats, the sort of painting has a time value as primitive work.

Gazir Gan songs to a legendary saint popularly known as Gazi Pir. Gazi songs were particularly popular in the districts of faridpur, noakhali, chittagong and sylhet. They were performed for boons received or wished for, such as for a child, after a cure, for the fertility of the soil, for the well-being of cattle, for success in business, etc. Gazi songs would be presented while unfurling a scroll depicting different events in the life of Gazi Pir. On the scroll would also be depicted the field of Karbala, the Ka'aba, Hindu temples, etc. Sometimes these paintings were also done on earthenware pots.

The lead singer or gain, wearing a long robe and a turban, would twirl an asa and move about in the performance area and sing. He would be accompanied by drummers, flautists and four or five dohars or choral singers, who would sing the refrain.

Gazi songs were preceded by a bandana or hymn, sung by the main singer. He would sing: 'I turn to the east in reverence to Bhanushvar (sun) whose rise brightens the world. Then I adore Gazi, the kind-hearted, who is saluted by Hindus and Mussalmans'. Then he would narrate the story of Gazi's birth, his wars with the demons and the evil spirits, as well as his rescue of a merchant at sea.

Although Gazi Pir was a Muslim, his followers included people from other religious communities as well. Many Gazi songs point out how people who did not respect him were punished. At least one song narrates how Gazi Pir saved the peasantry from the oppression of a zamindar. Another song describes how a devotee won a court case. In Gazi songs spiritual and material interests are often intertwined. The audience give money in charity in the name of Gazi Pir. This genre of songs is almost extinct in Bangladesh today. [Ashraf Siddiqui]

The tradition of Gazir pat can be traced back to the 7th century. It is also possible that the scroll paintings of Bangladesh are linked to the traditional pictorial art of continental India of the pre-Buddhist and pre-Ajanta epochs, and of Tibet, Nepal, China and Japan of later times.5. Civilisations are built on the exchange and encounter of different cultural traditions

One of the most striking exhibits in the current British Museum exhibition Myths of Bengal is the beautiful Gazi scroll - not just for its rich colours and vivid figures, but because it illustrates the enriching coexistence of two of the world's great faiths. Images of Hindus making puja offerings are juxtaposed with those of Muslims making similar offerings at the tombs of their saints (pirs). It shows how a remarkable, syncretic culture emerged in which the tombs of many pirs became places of pilgrimage for both Hindus and Muslims.

The syncretism is also evident in the Bengali tradition of bauls, itinerant singers who came from both faiths and used the same songs, full of the yearning of the humble man for God. These songs were a great inspiration to the Bengali Hindu poet Rabindranath Tagore (whose paintings are also on show at the British Museum) and expressed the same sentiments found in both religious traditions. The national anthems of the predominantly Muslim country of Bangladesh and the predominantly Hindu country of India were both written by Tagore.

In his most recent book, Identity and Violence, Amartya Sen, a Bengali, describes how civilisations are built on the exchange and encounter of different cultural traditions. It is both an impoverishment and a deeply dangerous development to recast the identity of regions in terms of just one faith. He cites Tagore, who described his family background as a "confluence of three cultures, Hindu, Mohammedan and British".

Bengal has been one of the world's great melting pots, perhaps the place where east has met west for the longest period of settled coexistence. For more than 200 years it was at the heart of Britain's power in India, and Calcutta was the second city of the British empire. British rule brought shocking misgovernment, such as the Bengal famine of 1943 and economic exploitation, but it also brought western ideas, producing a vibrant cultural life in the 19th century.

Vestiges of the syncretism survive, despite the fact that West Bengal is now largely Hindu, and Bangladesh Muslim, but the process of erosion grinds on. In both countries, wealthier diasporas exacerbate the sharpening of antagonistic religious identities. The faith of huge numbers of Bangladeshi migrant workers now owes more to a global Islam influenced by Saudi Arabia than to Bengal's traditional Sufism. Upward social mobility in the villages of Sylhet - the region from which most British Bangladeshis come - is associated with a rejection of the folkloric piety in which even Bengal's pre-Islamic Buddhism was discernible.

Looking at the Gazi scroll, one cannot but conclude that the past offers more enlightened models of living with difference than we are achieving.

We need to be reminded - and inspired - by the history of places such as Bengal so that we can guard against the easy simplification that human beings can be parcelled into discrete civilisational categories based on faith. Some of the world's richest cultural traditions are the legacy of the interaction of several faiths (Madeleine Bunting Wednesday November 29, 2006,The Guardian) .6.Save 'Patachitra' 'scroll painting'- Our National Heritage

'Patachitra' or 'scroll painting', one of the age-old forms of popular art, has existed in Bangladesh since the 12th century. These patas depicted scenes from religious stories and cultural myths and themes from life in rural Bangladesh. Shambhu Acharya, a 'patachitra' artist from Bikrampur has in recent years received the attention and appreciation from a few art lovers and cultural activists. Shambhu Acharya was born in 1954. His father was Patua Shudhir Chandra Acharya and mother was Kalpana Bala Acharya who herself was an Alpona painter. His family has been practising patachitra for more than 400 years. The themes of their paintings include stories of Gazir Pata Sree Krishna, Muharram, Ramayana, Mahabharata, Manasha Mangal, Rass Leela and also various others themes from our local folk culture.

He uses all local materials for his paintings. For the canvas, Shambhu uses 'markin' cloth and the age-old techniques. The cloth is first layered with mud or cowdung and dried, it's then layered again with a paste made from tamarind seeds and powder of brick and chalk. Thus, surfaces of the patachitra canvas which is called 'doli' is prepared. This canvas lasts for ages.

For making his colour he uses black ink made from the smoke of lamp flames, zinc oxide, vermilion, egg yolk, the sticky juice of wood apples, sabu dana and various kinds of earth colour such as gopi mati,tilok mati, dheu mati, ela mati and raja neel (blue).

Unfortunately this recognition has mostly been confined to only a few connoisseurs of art living in the capital city and some places abroad where he held exhibitions, while most people of his own country know very little about Shambhu Acharya and the thousands of years' old art form that his family has been practising for more than 400 years.

The earliest 'patuas' (as the artists of scroll paintings are called) usually took the themes for their paintings from the Mahabharata, Ramayana, various legends, myths and religious stories , and later expanded the range by including many popular and secular stories of the land. One of the most popular themes of the 'patachitra' was the Gazi's Pat depicting the courageous deeds and conquests of Ismail Gazi, a Muslim general who served the Sultan Barbak in the 15th century.

Patachitra, like many other popular folk art of Bengal such as pottery, the weaving of the Muslin and i, and jatra, was practised in families through generation after generation. The skills and the commitment to the art form were handed down from fathers to their sons.Shambhu Acharya, the patua, comes from such a long line of dedicated patuas of Bikrampur. His family has been working in this art form for the last eight generations. But it's only the art of Shambhu, the 9th generation of patuas, which has recently come to the limelight. The modern urban people of today are striving to find the roots of their traditional culture. Perhaps this well help to establish the art of patachitra once again with all its glory and popularity'.

It is amazing to think how a family has been struggling to practise this art form in a place like Bikrampur for so many generations. There are many artists like Shambhu Acharya about whom very few of us know. It is our responsibility to search for and promote such talents in any field anywhere (Daily Star, September 16, 2006).

7. Save Traditional Bengali Dolls- Our National Heritage

Like the rural folk-painters and potters of Bengal, Jamini Roy used cheap indigenous pigments for his art to make them within the reach of the affluent as well as the poor. Like the pata-painters of Bengal he proposed his own paintings from indigenous materials like lampblack, chawk-powder, leaves and creepers. Even today, modern paintings of Jamini Roy, executed in the ideal of folk-pata paintings and dolls, attract the connoisseur's eyes as well as the teeming multitude

A figurine of a dancing girl was discovered at Mohenjodaro. Excavations elsewhere have unearthed clay dolls, very similar to the mother goddess figures that village women form even today with a soft lump of clay. Dolls have also been unearthed at savar, mainamati, mahasthan and dinajpur in Bangladesh. Apart from human figures, animal and bird forms have also been discovered at these sites.

Clay dolls perhaps emerged from the potter's work of making images of gods and goddesses. These may be shaped by hand or made in moulds. It is easier and quicker to mould dolls. Ornamentation and costumes are drawn by means of pointed sticks. Handmade dolls are not painted, but dried in the sun and fired in kilns.

Moulds for making dolls are generally handed down, though new designs of moulds are also made. Dolls made in moulds are painted in various colours after they are fired. Common colours are white, blue, yellow, green, and black. mymensingh is famous for doll-making as are Savar, dhamrai and Rayerbazar.Wooden dolls are also traditional and are usually made from kadam, amda, shyaoda, and shimul. Artisans shape the wood into triangular and semi-circular pieces to make the figures of women. The bodies of the dolls are painted as well as their dresses and ornaments. Colours commonly used are yellow, red, green and black. These female dolls are called 'mummy dolls' since they look like Egyptian mummies

Dolls - Our Heritage

by Abanindranath Tagore

Leader of the Revivalist Movement in the field of Modern Indian Painting in Bengal, Abanindranath Tagore is also credited with a key contribution towards ushering in the renaissance in Indian painting. Born on 7th August, 1871, at Jorasanko, at the family residence of the aristocratic Tagores, Abanindranath grew up in a family environment of multi-hued creativity, as the Tagores culturally spearheaded Calcutta in those days.

In 1907, Tagore established the Indian School of Oriental Art and founded ‘The Bengal School’, which was responsible in pioneering the Bengal Revivalist movement. Under his guidance, a new generation of painters was raised, like Nandalal Bose, Asit Halder, Kshitindranath Majumder and Jamini Roy, S.N.Gupta and a host of others. Nandalal Bose (1882-1966), one of his most outstanding students, revived the study and practice of art in India, later in life.

In his own way, Abanindranath also contributed to the Freedom struggle. Money was raised for the National Fund by singing processions who carried his painting, Bharat Mata, made into a flag. He also contributed handloom cloth from Jessore and Pabna to the swadeshi store. Abanindranath Tagore, regarded as the father of India's modern art, died in 1951_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

We have dolls as playthings for children; marionettes for play-acting of larger size; life -size, and sometimes larger than life, caricatures, effigies and clowns.

Toy dolls are about span high, thumb long, and smaller, down to the miniature size.Clay, wood, pith and paper are the materials of which our dolls are made.

Toy dolls are first made in the rough by the potter or carpenter, whereupon the decorator steps in to do up the features and put in the colouring, before they finally find their way to the shops.

The making of idols for worship is much on the same lines.

The potter makes the figure according to tradition, with dress folds, ornaments, and crown, complete.

The decorator then adds the colouring of body, features and robes, the tinsel halo and other appurtenances.

In the case of the play-acting marionettes, the carpenter makes the body and limbs separately, and the play- actor loosely fastens the limbs to the body with strings, so that they may be moved as required.

The dresser follows, colouring and dressing them up, on the eve of the performance, for the parts they are intended to play.

The animals and birds that are to come on the stage are designed by the carpenter on a common pattern, and subsequently made up to suit the occasion…the addition of mane or stripes, for instance, converting the same dummy into lion or tiger.

This kind of co-operation between the several artists is made to serve all the purposes of the play.There are mainly three kinds of dolls or toys:

Immobile-such as a figure of Ganesh, or a fat woman-figure with a stump in place of legs to be dressed up by the playing child. Partly mobile - such as palm-leaf sepoys with jointed arms and legs jerked into martial attitudes by strings attached to a bamboo spring; pith birds and fishes, dangling on strings from a supporting frame, swaying to the breeze. Toys on wheels - such as clay carts, wooden or metal horses; etc.

Whistling tin birds or squeaking celluloid babies are beyond the resources of our toy makers. Our marionettes go through their movements in obedience to the string-pulling of the play actor and do their squeaking by proxy through his assistant.

A Doll from Bengal

This is a typical wooden doll found all over Bengal. It varies in its decorations and colours in different districts but the form remains the same. This particular one was bought in Kenduli in Birbhum district. The colour of the head, arms and feet is yellow. Upper garment covering the body below the waist is blue and green. The details and decorations of the figure are drawn with black and red thick brush lines.

Mr. Nandalal Bose says it is not possible for him to say when this toy was introduced in Bengal but the back of this toy resembles the back of the stone statues of Vishnu and other gods. He also feels that they somehow look like Egyptian mummy cases. Size of the original doll: 10 inches high x 3 inches wide approx.Our old doll types are no longer to be seen in all their variety; some have even changed their forms and decorations to suit modern taste. Some idea of the different kinds of dolls or toys that were in use may be gathered from our nursery rhymes. I give a few examples:

The Moon Doll: --"Moon on her arms, moons on her feet, a moon on her forehead doth shine." The Car of Thirteen Spires: --"O look sister, how wonderful! The confectioner over the way has made a car with thirteen spires, and a monkey holding the banner." The Nodding Old Man: --"The aged one's head nods and nods, with a myna perched on top." Gopal (Krishna): --"Who says Gopal is flat-faced I have brought clay from Sukhchar to make a straight nose for him. Who says Gopal is dark I have brought turmeric from Patna to make his complexion shine." Animals: --"The Shy Cat", "The Royal Elephant", "The Black and White Cats of Shasthi", etc. There are the Smiling Doll, the Jolly Doll, the Merry Doll, the Crying Doll, and other descriptions…the meanings of which cannot now be traced. There are the Smiling Doll, the Jolly Doll, the Merry Doll, the Crying Doll, and other descriptions…the meanings of which cannot now be traced. A Queen Doll made of fire-wood is still to be seen in Kalighat shops.The following portion of a fairy tale gives us a picture of the making of a doll queen:

"Four companions were going from one village to another. Dusk fell while they were passing through a wood before their journey's end, and they had to stay the night under a tree. The carpenter's son took the first watch. To while away the time he cut off a branch and carved a woman doll. The decorator's son took the second watch. He shaped the eyes and nose, gave golden colour to the body and rose colour to the palms and soles, and seated the naked doll under the tree. The weaver's son took the third watch and dressed her up, veil and all. The king's son woke last, and in the fourth watch chanted a magic spell, learnt from a holy man, which gave her life; then placing her in a palanquin, he took her away with him."Gods come on the scene, and engage in a terrific battle with demons, in the course of which the floor is strewn with headless trunks, whereupon all the dolls on the stage register different degrees of alarm; and so on…...

(Source: Visva-Bharati Quarterly, New Series, Vol. I, Part I, May-July, 1935.)

Bibliography

Gurusaday Dutt, Patuya Sangeet, University of Calcutta, Calcutta, 1939;

Benoy Ghosh, Traditional Arts and Crafts of West Bengal: A Sociological Survey, Papyrus, Calcutta, 1981;

Rajatananda Dasgupta, 'Bharatiya Upamahadeshe Patachitrakala', Bangladesher Lokoshilpa, ed, Syed Mahmudul Hasan, Bangladesh Folk Art and Crafts Foundation, Sonargaon. 1983;

Tofail Ahmad, 'Patuya Sudhir Acharya', Karushilpi Purashkar, Bangladesh Jatiya Karushilpa Parishad, Dhaka, 1989.

Jasim Uddin, Thakur Barir Aginay, Grantho Prakash, Kolkata, 1963

Visva-Bharati QuarterlyLast modified: January 22, 2008

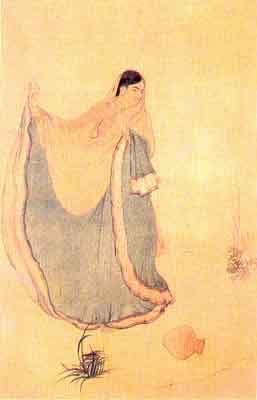

Behula is the heroine in the Bangla epic of Manasamangal. Manasamangal was written between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries. Though its religious purpose is that to glorify the Hindu goddess of Manasa, it is more well known for depicting the love story of Behula and her husband Lakhindar. Lakhindar's father angers Manasa, who causes Lakhindar to be bitten by a snake on his wedding night, though he and Behula are enclosed in an iron made house. Behula sails alone with her husband's dead body on a boat. She finally appeases the goddess and brings Lakhindar back to life. Behula continues to fascinate the Bengali mind, both in Bangladesh and West Bengal. She is often seen as the archetypal Bengali woman, full of love and courage.

Behula is the heroine in the Bangla epic of Manasamangal. Manasamangal was written between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries. Though its religious purpose is that to glorify the Hindu goddess of Manasa, it is more well known for depicting the love story of Behula and her husband Lakhindar. Lakhindar's father angers Manasa, who causes Lakhindar to be bitten by a snake on his wedding night, though he and Behula are enclosed in an iron made house. Behula sails alone with her husband's dead body on a boat. She finally appeases the goddess and brings Lakhindar back to life. Behula continues to fascinate the Bengali mind, both in Bangladesh and West Bengal. She is often seen as the archetypal Bengali woman, full of love and courage.

No comments:

Post a Comment